As Veterans Day approaches and the political landscape gears up for the 2024 presidential campaign, it’s an opportune moment to reflect on the legacy of veterans who have ascended to the highest office in the United States. Throughout American history, a significant number of presidents have served in the military, and their experiences in uniform have undeniably shaped their leadership and political trajectories. Among these distinguished leaders, the figure of the “President That Served In Ww1” holds a unique place, representing a pivotal era in global history and its impact on American leadership.

Of the 45 individuals who have held the presidency, an impressive 31 have a background in military service. This group includes leaders from various ranks and conflicts, showcasing the diverse military experiences that have informed the nation’s highest office. Ten presidents attained the rank of general, while five reached the rank of colonel. Their service spans from the Revolutionary War, which saw three future presidents in its ranks, to the War of 1812 (five presidents), the Mexican-American War (three presidents), the Civil War (five presidents), the Spanish-American War (one president), World War I (one president), and World War II (eight presidents). This rich tapestry of military engagement underscores the deep connection between military service and presidential leadership throughout American history.

Perhaps the most iconic veteran president is George Washington. His leadership of the Continental Army during the American Revolution was instrumental in securing independence. Washington then presided over the Constitutional Convention, laying the foundation for the U.S. government, and subsequently became the nation’s first president. His life was defined by leadership and achievement, guiding the nascent nation through war and shaping its foundational principles.

George Washington at Princeton

George Washington at Princeton

Washington’s most profound act, both as a military leader and statesman, was his voluntary relinquishment of power. He first resigned his commission as General of the Army after victory in the Revolution and later stepped down after two terms as president. His early address to the Virginia Regiment encapsulates his philosophy: “Remember, that it is the actions, and not the commission, that make the officer, and that there is more expected from him than the title.” This commitment to service over personal ambition set a powerful precedent for future leaders.

Abraham Lincoln’s military experience was less extensive than Washington’s, with only a year in the Illinois militia during the Blackhawk War. However, the title of Captain he earned at 23 years old remained a source of pride. He later recalled during his 1860 presidential campaign that this title was “a success which gave me more pleasure than any I have had since.” Lincoln’s presidency would become one of the most transformative in American history, marked by the abolition of slavery and the preservation of the Union during the Civil War.

Lincoln’s empathy for veterans was evident in his actions. He signed legislation establishing national facilities to care for wounded Civil War soldiers. His Second Inaugural Address, delivered on the East Front of the U.S. Capitol, resonated with compassion: “to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan.” These words continue to inspire the Department of Veterans Affairs, forming the bedrock of its mission statement today.

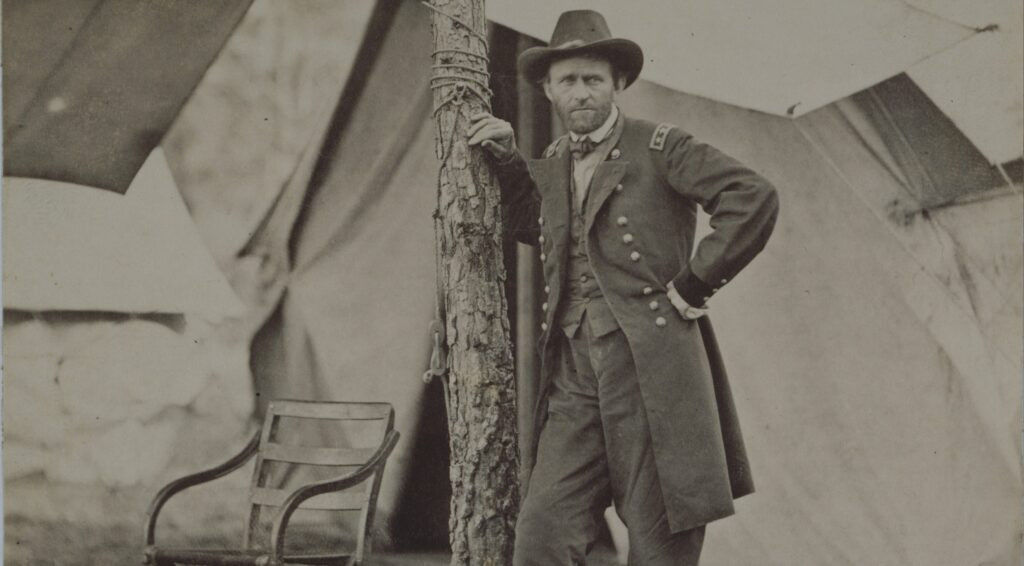

Ulysses S. Grant, who served as Lincoln’s commanding General, became president three years after the Civil War’s end. A West Point graduate and veteran of the Mexican War under Zachary Taylor, Grant was celebrated for his strategic brilliance and popularity among his troops. His aide-de-camp, Colonel Horace Porter, noted, “His soldiers always knew that he was ready to rough it with them and share their hardships on the march. He wore no better clothes than they, and often ate no better food.”

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant

Grant’s presidency faced challenges, including financial scandals, but he was instrumental in Reconstruction. He deployed federal troops to the South to combat the Ku Klux Klan’s violence and protect the newly gained rights of four million Black citizens. Grant’s autobiography, completed shortly before his death in 1885, revealed his complex view of conflict: “Although a soldier by profession, I have never felt any sort of fondness for war, and I have never advocated it, except as a means of peace.”

Sixteen years later, Theodore Roosevelt assumed the presidency, bringing his own distinct perspective on war, shaped by his experience leading the Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War. Roosevelt’s daring exploits, particularly his charge up San Juan Hill, were widely publicized and fueled his burgeoning political career upon his return.

As president, Roosevelt oversaw the construction of the Panama Canal, strengthened the U.S. Navy into a global power, and became known for his diplomatic philosophy: “Speak softly, and carry a big stick.” He championed physical fitness standards for the military and consistently advocated for veterans’ welfare. Roosevelt believed that those who risked their lives for the nation deserved exceptional respect and support. In a 1903 speech, he asserted, “A man who is good enough to shed his blood for his country is good enough to be given a square deal afterwards.”

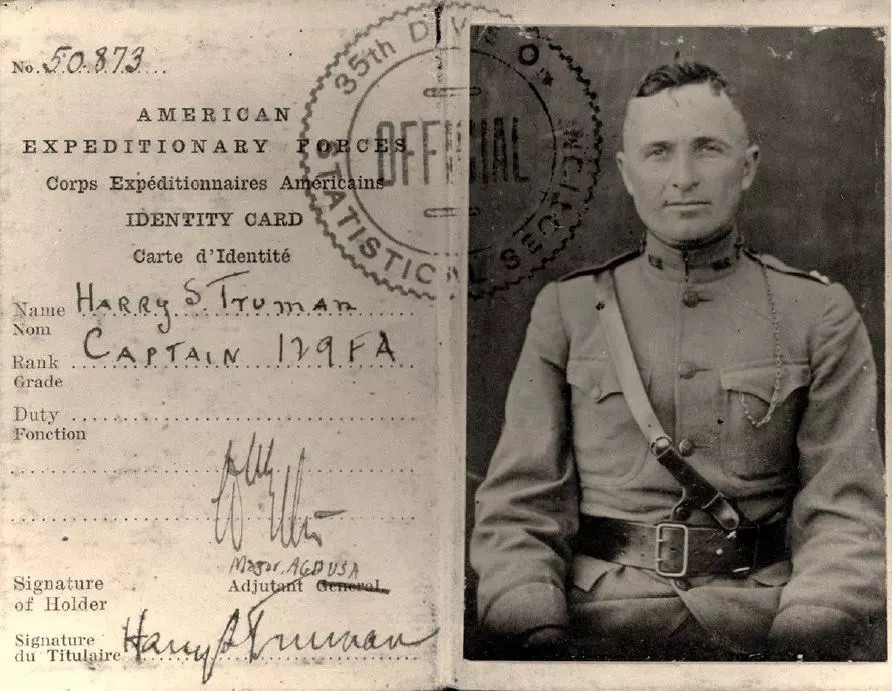

Harry Truman stands as the sole “president that served in ww1.” In 1917, at the age of 33, Truman, a farmer with prior business ventures, enlisted in the Army as America entered World War I. Despite being older than draft age, his leadership qualities quickly emerged. He was elected lieutenant of Battery D in the Missouri National Guard and was promoted to Captain during deployment to France. Truman earned a reputation as a firm yet just leader, dedicated to his troops and courageous in combat. His popularity was such that his men gifted him a loving cup inscribed with: “Presented by the Members of Battery D in appreciation of his justice, ability and leadership.”

Returning home a war hero, Truman entered politics. Veterans were a significant part of his support base. After serving as a judge, he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1934, focusing on military policy and defense spending. Franklin Roosevelt selected him as his Vice President in 1944. Upon FDR’s death, Truman, the farmer-turned-WWI captain, became president.

Truman’s presidency profoundly shaped the post-World War II world. He made the momentous decision to use atomic bombs to end World War II, ushering in the atomic age. He initiated the Marshall Plan to rebuild Europe, established the Truman Doctrine to contain communism, desegregated the military, and oversaw the GI Bill’s implementation. He also recognized Israel as a new nation. Truman never forgot his military roots. In his 1949 inaugural parade, he invited surviving members of Battery D to march with him. He later reflected, “My whole political career is based on my war service and war associates.”

Captain Harry Truman in WWI Uniform

Captain Harry Truman in WWI Uniform

Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower, Truman’s successor, also deeply understood the impact of military service on leadership. Eisenhower graduated from West Point in 1915 and served stateside during World War I, training recruits and steadily advancing in rank. Recognizing his potential, a superior officer encouraged him to attend the Command and General Staff School, where he graduated top of his class in 1926. He served under General John Pershing and later worked for the Assistant Secretary of War. In 1933, he became chief military aide to General Douglas MacArthur, accompanying him to the Philippines.

After Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was assigned to the War Department, where General George Marshall tasked him with managing the Pacific war. In 1942, he was sent to England to plan the European campaign, culminating in the Normandy invasion on June 6, 1944. As Supreme Commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces, Eisenhower was promoted to General of the Army in December 1944. He succeeded Marshall as Army Chief of Staff after the war in November 1945. In a 1946 address, he articulated his complex view of war: “I hate war as only a soldier who has lived it can, only as one who has seen its brutality, its futility, its stupidity.”

Despite initial reluctance, Eisenhower accepted the Republican presidential nomination in 1952 and won two terms in a landslide. His presidency saw the end of the Korean War, the creation of the interstate highway system, the launch of NASA, and the enforcement of school desegregation in Little Rock. He also signed legislation renaming Armistice Day to Veterans Day. Eisenhower’s farewell address in 1961 cautioned against the “military-industrial complex,” revealing his enduring perspective on war and peace.

Three days after Eisenhower’s farewell, John F. Kennedy, another World War II veteran, became president. Kennedy was a decorated war hero, receiving medals including a Purple Heart for his bravery after his PT-boat was sunk by a Japanese destroyer in 1943. Unlike Eisenhower, Kennedy was a junior officer, a 26-year-old Naval Lieutenant. He represented a new generation, a theme he emphasized in his Inaugural Address: “Let the word go forth that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace…”

Kennedy faced immediate challenges, including the Bay of Pigs invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Bay of Pigs fiasco led Kennedy to distrust military judgment. However, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, he disregarded recommendations to bomb Soviet missile sites, opting for a blockade, a strategy that proved successful.

Despite his skepticism towards the Pentagon, Kennedy respected military service. In a 1963 speech at the Naval Academy, he stated, “I hope that you realize how great is the dependence of our country upon the men who serve in our Armed Forces. I can think of no more rewarding a career.”

Lieutenant John F. Kennedy

Lieutenant John F. Kennedy

Thirty years later, in 1993, George H.W. Bush, another WWII veteran, echoed Kennedy’s sentiments in a speech at West Point: “There is no higher calling, no more honorable choice than the one that you hear today have made. To join the Armed Forces is to be prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice for your country and for your fellow man.”

Bush’s experience as a 20-year-old Navy pilot, who was shot down over the Pacific and served in a squadron with a high casualty rate, deeply influenced his life. He flew 58 combat missions and received multiple commendations for his heroism. His presidency, following a career in Congress, diplomacy, and as Vice President, was marked by the peaceful end of the Cold War and the first Gulf War. Bush’s presidency emphasized service, reflecting his words to the West Point cadets:

“What you have done, what you are doing, sends an important message, one that I fear sometimes gets lost amidst today’s often materialist, self-interested culture. It is important to remember — it is important to demonstrate — that there is a higher purpose to life beyond oneself. I speak of family, of community, of ideals. I speak of duty, honor, country.”

Duty. Honor. Country. As Veterans Day is commemorated, these words serve as a powerful reminder, honoring not only the presidents who were veterans but all who have served and continue to serve, defending the nation’s freedoms.

SMALL-Veterans-Who-Served-as-President-of-the-United-States Image