The Server Message Block (SMB) protocol is a cornerstone of network file sharing, enabling computers to access files, printers, and other resources across a network. Functioning as a client-server communication protocol, SMB has become indispensable, particularly within Windows environments, though its reach extends to Linux, macOS, and other operating systems. Developed initially at IBM in the 1980s, SMB has undergone significant evolution, resulting in various versions, or dialects, designed to meet the ever-changing demands of modern networks. It remains a dominant solution for file sharing in businesses and organizations globally.

Understanding the Functionality of the SMB Protocol

At its core, the SMB protocol facilitates application and user access to files residing on remote servers. Beyond file sharing, it also supports connections to printers and other network resources. SMB empowers client applications with a secure and structured approach to manage files on servers, including operations like opening, reading, moving, creating, and updating. Furthermore, it allows communication with server-side programs engineered to respond to SMB client requests.

Operating on a request-response model, SMB is a widely adopted method for network communication. A client initiates communication by sending an SMB request to the server. Upon receiving this request, the server responds with an SMB response, establishing a communication channel for bidirectional data exchange.

The SMB protocol functions at the application layer of the network model but depends on lower-level network protocols for data transport. Initially, SMB operated over NetBIOS over TCP/IP (NBT), utilizing ports 137, 138, and 139. However, modern SMB implementations primarily run directly over TCP/IP, leveraging Server Message Block Port 445.

Server message block port 445 is now the standard port for direct SMB communication over TCP/IP, offering a more efficient and streamlined approach compared to the older NetBIOS-based methods. For devices that do not support SMB directly over TCP/IP, NetBIOS over TCP/IP might still be necessary, utilizing the legacy ports.

SMB request and response

SMB request and response

Since Windows 95, Microsoft Windows operating systems have incorporated both client and server-side SMB protocol support. Similarly, Linux and macOS platforms offer native SMB support. Unix-based systems can utilize Samba to enable SMB access for file and print services, ensuring cross-platform compatibility.

It’s important to note that SMB clients and servers may support different SMB dialects. In such cases, systems negotiate the dialect to be used at the start of a session to ensure seamless communication.

The Evolution of SMB Protocol Dialects

Over its lifespan, the SMB protocol has seen the introduction of numerous dialects, each bringing enhancements in capabilities, scalability, security, and efficiency. Key SMB dialects include:

- SMB 1.0/CIFS: The original dialect, now considered outdated and insecure.

- SMB 2.0: Introduced significant performance improvements and reduced chattiness compared to SMB 1.0.

- SMB 2.1: Further performance optimizations and feature enhancements.

- SMB 3.0: Marked a major step forward in security, introducing features like end-to-end encryption.

- SMB 3.0.2: Minor updates and refinements to SMB 3.0.

- SMB 3.1.1: The latest stable dialect, offering enhanced security with pre-authentication integrity and improved encryption negotiation.

Security Considerations for SMB and Server Message Block Port

In 2017, the WannaCry and Petya ransomware attacks highlighted critical vulnerabilities within SMB 1.0. These attacks exploited weaknesses to deploy malware and propagate it across networks, causing widespread disruption. While Microsoft released patches to address these vulnerabilities, security experts strongly recommend disabling SMB 1.0/CIFS on all systems due to its inherent security risks.

In contrast, SMB 3.0 and later dialects incorporate robust security measures. SMB 3.0 introduced end-to-end data encryption, safeguarding data from eavesdropping. It also implemented secure dialect negotiation, mitigating man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks. SMB 3.1.1 further strengthened security by enhancing encryption capabilities and adding pre-authentication integrity.

Given the security vulnerabilities associated with older dialects, especially SMB 1.0, it is crucial to ensure systems are running modern, secure SMB versions and that server message block port 445 is properly secured and monitored. Disabling SMB 1.0 and enforcing the use of newer dialects are essential security best practices.

CIFS, SMB, and Samba: Clarifying the Terminology

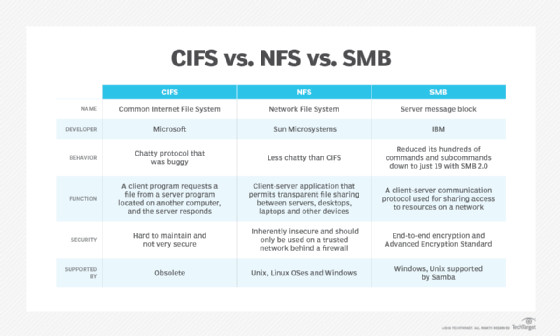

CIFS (Common Internet File System) is often discussed alongside SMB. In reality, CIFS is an early dialect of the SMB protocol, specifically SMB 1.0, developed by Microsoft. Although sometimes used interchangeably, CIFS technically refers to this specific, older implementation. However, in practice, technical documentation and application interfaces might use the terms SMB and CIFS synonymously, particularly when referencing SMB 1.0/CIFS.

Understanding the distinction between dialects is vital, especially concerning security. SMB 1.0/CIFS lacks the advanced security features present in later dialects like SMB 3.0 and above.

CIFS vs. NFS vs. SMB

CIFS vs. NFS vs. SMB

Samba, launched in 1992, is an open-source implementation of the SMB protocol designed for Unix and Linux systems. Samba enables interoperability between Windows and Linux/Unix environments, allowing various clients to access SMB resources on different operating systems. Samba facilitates file sharing, print services, authentication, and name resolution between Linux/Unix servers and Windows clients. It also enables integration of Linux/Unix servers into Active Directory environments.

Conclusion: The Enduring Role of SMB and Server Message Block Port

The Server Message Block protocol remains a fundamental technology for network file sharing. From its origins in the 1980s to its modern iterations, SMB has continuously evolved to meet the demands of contemporary networks. Understanding server message block port 445 and the importance of using secure, up-to-date SMB dialects is crucial for maintaining secure and efficient network operations. As networks continue to grow in complexity and security threats evolve, the SMB protocol, particularly when properly configured and secured, will continue to play a vital role in enabling seamless resource sharing across diverse computing environments.