The Traditional Latin Mass, now often termed the Extraordinary Form, holds a unique fascination, especially for younger generations discovering the rich liturgical heritage of the Catholic Church. For those who grew up with it, like a reader who shared his memories as an Altar Server in the 1960s, it wasn’t a “form” – it was simply the Mass. His reflections offer a poignant look into a time of significant liturgical transition, a period where the familiar rites began to evolve, sometimes subtly, sometimes dramatically. This is the story of those changes as witnessed through the eyes of a young altar server in suburban Los Angeles.

First Steps at the Altar: A Young Server’s Initiation

His journey began at the age of nine, fueled by an eagerness to participate more deeply in the Mass he attended daily before school. Despite the parish rule that altar servers should be at least ten, his persistence paid off, thanks to Sister Mary Eileen, the director of altar servers. Sister Mary Eileen, perhaps hoping to deter his youthful enthusiasm, challenged him to learn the Latin responses. Armed with a holy card inscribed with these responses, a tool he treasures even in memory, and his St. Joseph Daily Missal, already familiar from daily Mass attendance since the age of eight, he quickly mastered the Latin. This early dedication marked the beginning of years of service at the altar, a commitment that would extend through high school and eventually lead him to St. John’s Seminary College.

Young altar servers assisting priest during Latin Mass

Young altar servers assisting priest during Latin Mass

An Era of Transition: Vatican II and the Winds of Change

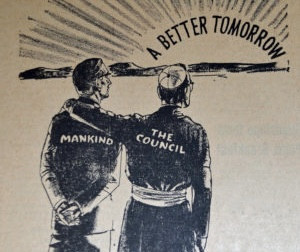

The 1960s were a transformative decade, not just in society but profoundly within the Catholic Church. The election of Pope John XXIII and the announcement of the Second Vatican Council signaled the beginning of this era. He recalls a parish priest visiting his third-grade classroom to explain the upcoming Ecumenical Council, though the specifics are now lost to time. However, a church pamphlet about the Council remains a tangible reminder of those days. As an altar server, he diligently followed the schedule printed in the parish bulletin, serving weekly shifts, including Tuesday evening Mother of Perpetual Help novenas and Benediction – a weekly event affectionately termed a “novena” by the parish staff, despite its regularity.

Adventures and Accidents: The Thurifer’s Tale

Serving as a thurifer during Forty Hours Devotion provided a memorable, if slightly alarming, anecdote. In the pre-self-lighting charcoal era, lighting the coals for the thurible was a task requiring careful attention. During one Rosary service preceding Benediction, a piece of lit charcoal, unbeknownst to him, found its way into the sleeve of his cassock. As he knelt behind the priest during the Tantum Ergo, the burning coal made its presence known, leaving a red ring and a hole in his sleeve. The pastor, witnessing the incident, swiftly extinguished the small fire. This story became parish lore, marking him as “the altar boy who caught fire,” a humorous yet vivid memory of the hands-on experiences of altar service in that period.

The Responsibilities of a Pre-Vatican II Altar Server

In his parish, altar servers were integral to the Mass preparation. Unlike today, where lay volunteers or adults often handle these tasks, young servers were responsible for setting the altar: placing the Missal, preparing the cruets, arranging the finger towel, Lavabo bowl, and Communion patens on the credence table. These duties instilled a sense of responsibility and deeper engagement with the liturgy. Sunday Masses, considered more solemn, were typically served by the “big boys,” seventh and eighth graders, partly due to the heavier Missal stand used. Red cassocks were worn on Sundays, black on weekdays, adding to the visual distinction of liturgical celebrations.

Subtle Shifts: The Gradual Evolution of the Liturgy

The initial changes from the Council were subtle, almost imperceptible to a young server. Starting around 1962, when he was in seventh grade, small alterations began. The first was the inclusion of St. Joseph in the Canon of the Mass, a change that later became part of Eucharistic Prayer #1. Then, the second Confiteor before Communion was removed, followed by the omission of Psalm 42 at the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar and the Last Gospel. At the time, these changes seemed minor, isolated adjustments. However, in retrospect, they were the beginning of a more significant transformation.

The Unveiling of the New Mass: A Gradual Transition

The cumulative effect of these incremental changes was not immediately apparent. It was a slow process, like “raising the water temperature slowly in a bucket so that the frog won’t notice he’s being cooked.” Cardinal McIntyre of Los Angeles, his Ordinary, was hesitant to implement changes rapidly, further contributing to the gradual nature of the liturgical shift in their diocese. By his senior year of high school, the vernacular had largely replaced Latin in the Mass. He recalls that in his junior year, the Collect, Secret, and Postcommunion were still in Latin, transitioning to English by graduation. Altar cards remained on the altar, a vestige of the Latin prayers, even as English became more prevalent in the liturgy.

Seminary and the “Change of the Month Club”

The liturgical evolution continued into his seminary years. In the spring of 1969, services were temporarily moved to the Prayer Hall as the altar was moved away from the wall – a physical manifestation of the liturgical changes taking place. By 1971, the new Eucharistic Prayers, initially in Latin, were introduced, preceding the ICEL translations. The pace of change felt relentless. A classmate sardonically dubbed these continuous alterations the “change of the month club.” The new Lectionary followed, further reshaping the liturgical landscape.

A Sense of Loss: Reflecting on a Changed Liturgy

Looking back, the experience is marked by a profound sense of loss. The built-in reverence of the Traditional Latin Mass, once taken for granted, was gradually eroded. This erosion, experienced firsthand from the vantage point of the altar, left a lasting impression. The sentiment is perhaps best captured by the analogy: “the worst TLM is better than the best Novus Ordo,” echoing the feeling that something irreplaceable was lost in the liturgical changes. While acknowledging the journey to the diaconate as a separate chapter, his memories as an altar server in the sixties remain a powerful testament to a period of profound liturgical transformation, a time when the Mass, as he knew it, changed in ways he could not have foreseen as a boy serving at the altar.