On July 17, 2023, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a ruling in Hunley v. Instagram, LLC that has significant implications for online content publishers, particularly those embedding content from platforms like Instagram. The court reaffirmed the “server test,” a legal principle that shields websites from copyright infringement liability when they embed images hosted on another website’s server. This decision, while upholding established precedent within the Ninth Circuit, arrives amidst ongoing legal debates and challenges to the server test in other U.S. jurisdictions. Understanding the nuances of this ruling is crucial for anyone involved in digital content creation and distribution.

Understanding Content Embedding and the Server Test

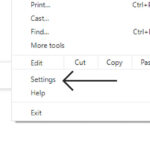

Content embedding, also known as in-line linking or framing, is a common practice on the internet. It allows websites to incorporate content, such as images or videos, from other sources directly into their pages without actually hosting that content themselves. Think of embedding an Instagram post into a blog article: the post appears seamlessly on the blog, but the actual image files remain stored on Instagram’s servers. This is achieved through HTML code that instructs the user’s browser to retrieve the content from the host website – in this case, the Instagram Server – and display it within the embedding website. Crucially, the embedding website doesn’t store a copy of the embedded content. The control over the content remains with the host website, like Instagram. They can decide whether embedding is permitted, and any changes or removals on the host site will be reflected wherever the content is embedded.

The legal framework around embedding and copyright has been largely shaped by the “server test,” established in 2007 by the Ninth Circuit in Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc. This test states that embedding content does not constitute a “display” under the Copyright Act. According to this test, only the website hosting the content on its server, such as the instagram server hosting Instagram posts, is considered to be “displaying” the content and potentially liable for direct copyright infringement. This ruling provided a significant degree of legal certainty for websites, allowing them to embed content without necessarily needing to secure licenses or fear direct infringement lawsuits.

Challenges to the Server Test and Legal Uncertainty

Over the past decade, the server test has faced increasing scrutiny and challenges, particularly in district courts outside the Ninth Circuit. Several courts have rejected the server test, arguing that websites embedding content are liable for direct copyright infringement. These decisions, including cases like Leader’s Inst., LLC v. Jackson, Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, LLC, Nicklen v. Sinclair Broad. Grp., Inc., and McGucken v. Newsweek LLC, created a split in legal opinion and significant uncertainty for online publishers.

This legal ambiguity forced websites to navigate a complex landscape. While defenses like “fair use” or arguments based on social media platform terms of service were raised, courts often dismissed these early in proceedings, leading to costly discovery and potential trials. Faced with legal risks and expenses, many websites adopted a cautious approach, avoiding embedding content unless explicit permission was obtained or a robust fair use argument could be made. This chilling effect hampered the free flow of information and content sharing online.

Hunley v. Instagram, LLC: Reaffirming the Server Test

The Hunley v. Instagram, LLC case emerged from copyright claims by two photographers against news websites that embedded their Instagram posts. Instead of directly suing the news websites for copyright infringement, the photographers targeted Instagram, alleging secondary infringement. However, Instagram’s secondary liability hinged on whether the news websites themselves were directly infringing copyright through embedding. This setup directly challenged the server test and its applicability to platforms like Instagram. The district court, relying on Perfect 10, dismissed the complaint, and the photographers appealed to the Ninth Circuit.

The Ninth Circuit in Hunley firmly upheld the server test. The court reiterated Perfect 10‘s interpretation of the Copyright Act, stating that for a “display” to be actionable under copyright law, it must involve displaying a “copy” of the copyrighted work, and that copy must be stored on the displaying computer’s server. Since embedding websites do not store a copy of the image – it remains on the instagram server or other host server – they are not “displaying” a copy under the Copyright Act and thus cannot be held directly liable for copyright infringement.

The photographers in Hunley presented several arguments against the server test. They argued it should be limited to search engines and algorithmic platforms, not broadly applied to all websites. The court rejected this, stating Perfect 10 made no such distinction. They also pointed to the contrary rulings in other jurisdictions. However, the Ninth Circuit emphasized that no other circuit court had overturned Perfect 10, and indeed, some had cited it favorably.

A key argument raised by the photographers was that the server test was incompatible with the Supreme Court’s decision in American Broadcasting Cos. v. Aereo, Inc. Aereo dealt with a company retransmitting broadcast television. The Supreme Court, in that case, focused on the practical effect of Aereo’s actions, rather than technical details, finding them to be infringing. The photographers argued Aereo‘s emphasis on practical realities should override the server test’s technical focus on where the copy is stored.

The Ninth Circuit disagreed. It clarified that Aereo addressed “public performance” rights under copyright law, distinct from the “public display” rights at issue in Perfect 10 and Hunley. Displaying a work requires showing a copy, while performance does not. Therefore, Aereo‘s interpretation of performance rights did not undermine Perfect 10‘s server test for display rights. The court also cautioned against over-interpreting Aereo‘s emphasis on practicalities, noting it was specific to the cable-TV-like context of the Aereo case.

Finally, the Ninth Circuit panel acknowledged policy arguments against the server test but stated that they were bound by the precedent of Perfect 10. They emphasized that any changes to the server test would need to come from an en banc rehearing by the full Ninth Circuit, the Supreme Court, or legislative amendments to the Copyright Act. Ultimately, the Ninth Circuit affirmed the dismissal of the Hunley complaint, reinforcing the server test within its jurisdiction and protecting websites embedding content from direct copyright liability in such cases.

Key Takeaways and Future Considerations

Hunley v. Instagram provides temporary reassurance for websites operating within the Ninth Circuit that rely on embedding content, including content from platforms like instagram server. The server test remains the governing legal principle in this circuit. However, this legal landscape is far from settled. The photographers in Hunley are seeking an en banc rehearing, which could lead to the Ninth Circuit reconsidering the server test.

Moreover, the Hunley decision primarily addresses image embedding. The court explicitly noted that the server test’s applicability to streaming videos or audio is less clear. Copyright law distinguishes between “display” and “performance” rights. The server test hinges on the idea that embedding an image doesn’t create a “copy” on the embedding website for “display” purposes. However, “performance” rights, which cover videos and audio, do not necessarily require a copy. This opens the door for potential future legal challenges arguing that embedding videos, even from platforms like instagram server, could constitute direct copyright infringement, even within the Ninth Circuit.

Despite the reaffirmation of the server test, the Ninth Circuit also referenced the “volitional conduct” requirement in copyright law. This principle suggests that direct copyright infringement requires some level of direct action causing the infringement. The court suggested that embedding websites merely provide “access” to content, while the host website (instagram server, for example) is the one actually copying and displaying the content. This “volitional conduct” reasoning could potentially extend the server test’s protection to embedded videos as well, arguing that embedding, whether images or videos, is not sufficiently “volitional” to constitute direct infringement. The Seventh Circuit has used similar logic in cases involving embedded videos.

Nevertheless, Hunley is binding only within the Ninth Circuit. For websites operating nationwide, the legal uncertainty persists. Embedding content, especially from platforms like instagram server, carries potential copyright risks outside the Ninth Circuit. Therefore, until there is a clear nationwide legal consensus, websites should exercise caution. Securing licenses for embedded content and carefully evaluating fair use defenses remain prudent steps. The legal landscape of online content embedding is still evolving, and ongoing vigilance is essential.