By 1798, George Washington’s contributions to the United States were already monumental. He had led the Continental Army to victory during the Revolutionary War, played a crucial role in shaping the Constitution, and served as the nation’s first president for two terms (1789–1797). Even after retiring from the presidency, his service was still sought after. President John Adams called upon him in July 1798 to become chief officer of the US Army, anticipating potential conflict with France. Washington, though desiring retirement, accepted this call to duty.

A year later, as the next presidential election approached in June 1799, Jonathan Trumbull Jr., then governor of Connecticut and a former military secretary to Washington, penned a letter urging him to consider a third term. Trumbull conveyed the hopes of many, writing, “should your Name again be brot up . . . you will not disappoint the hopes & Desires of the Wise & Good in every State, by refusing to come forward once more to the relief & support of your injured Country.” He expressed concern that the upcoming election might have a “very illfated Issue” without Washington at the helm.1

However, George Washington had compelling reasons to decline a third term, reinforcing the precedent for a two-term limit that would become a cornerstone of American presidential history.

Washington’s Reasons for Not Seeking a Third Term

Several factors weighed heavily in Washington’s decision to forgo another presidential run. These ranged from personal desires to profound concerns about the burgeoning political landscape of the young nation.

Promise and Principle: Avoiding the Perception of Power-Seeking

One significant reason was Washington’s commitment to the principle of limited government and his aversion to being perceived as power-hungry. He had, from the outset of his public service, aimed to avoid any semblance of monarchy or overreach. Running for a third term could be interpreted as clinging to power, contradicting his ideals. As Washington wrote to Trumbull, he wished to avoid being “charged . . . with concealed ambition.”

The Allure of Retirement: “The Vale of Life in Retirement”

Perhaps understandably after decades of relentless public service, Washington longed for personal peace and tranquility. He expressed “ardent wishes to pass through the vale of life in retiremt, undisturbed in the remnant of the days I have to sojourn here.” The desire for a quiet retirement at Mount Vernon was a powerful motivator in his decision to step away from the presidency permanently.

The Divisive Political Climate and the Rise of Parties

Beyond personal considerations, Washington was deeply troubled by the escalating partisan divisions within the United States. He observed with concern the increasingly hostile nature of political discourse. “The line between Parties,” he lamented in his letter to Trumbull, had become “so clearly drawn” that political actors disregarded “truth nor decency; attacking every character, without respect to persons – Public or Private, – who happen to differ from themselves in Politics.”

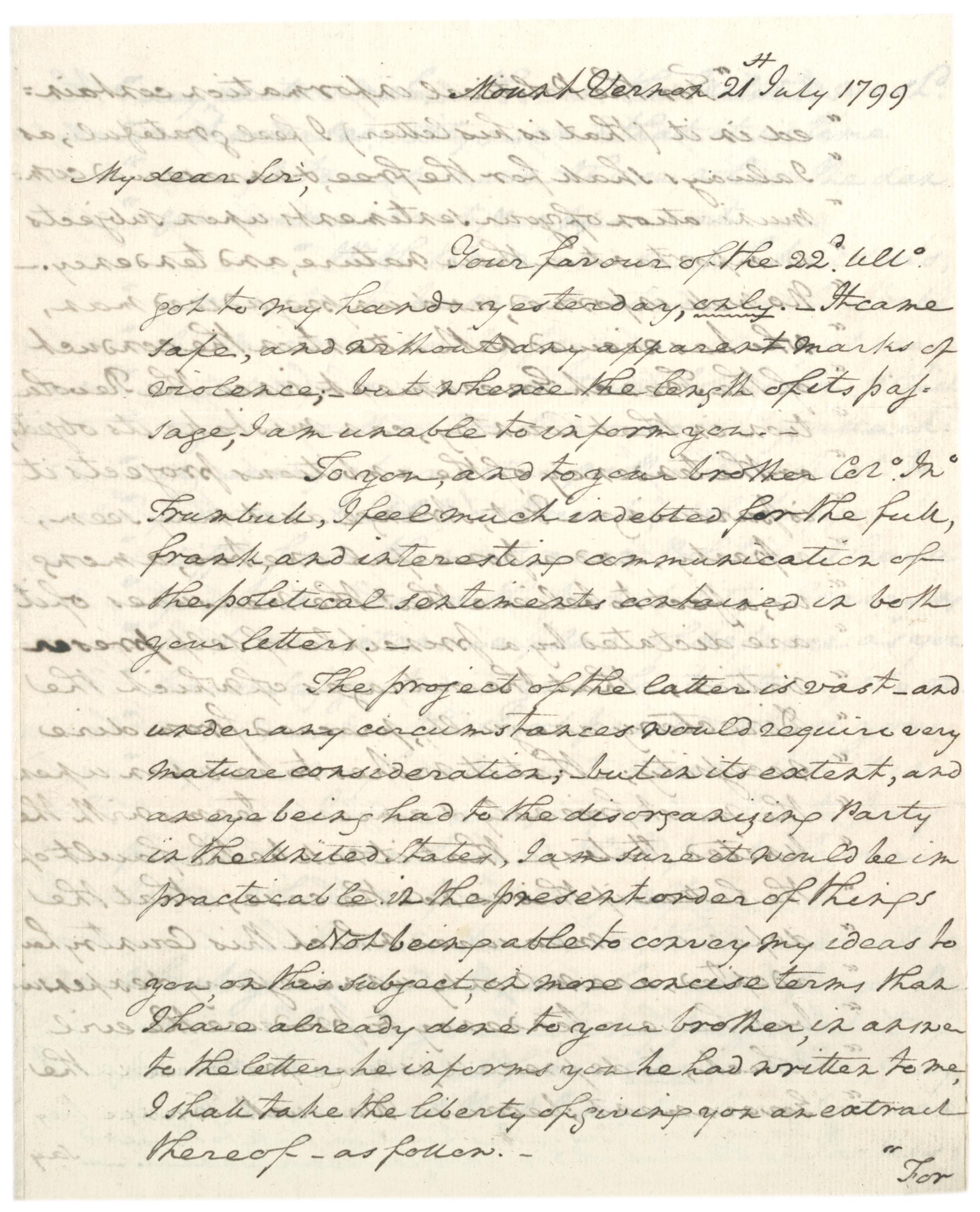

George Washington Letter to Jonathan Trumbull Jr.

George Washington Letter to Jonathan Trumbull Jr.

Washington, identifying as a Federalist, believed the intense partisanship would prevent him from gaining support beyond his own faction. “I am thoroughly convinced I should not draw a single vote from the Anti-federal side,” he stated. This political polarization, fueled by the emerging Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, worried Washington. He feared, as he had warned in his 1796 Farewell Address, that “unprincipled men” would exploit these divisions “to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government.” His famous, somewhat cynical remark about the opposing party – “Let that party set up a broomstick, and call it a true son of Liberty…and it will command their votes in toto!” – underscored his deep unease with the direction of American politics.

Washington’s Enduring Legacy: Setting the Two-Term Precedent

Despite the urging of prominent figures like Trumbull, George Washington firmly declined to seek a third term as president. His decision was rooted in a combination of personal desires and profound political principles. While always willing to serve his nation when called upon, as evidenced by his acceptance of the army commission in 1798, he believed that stepping aside from the presidency after two terms was crucial for the long-term health of the republic.

By choosing not to run again, George Washington established a powerful precedent for the peaceful transfer of power and the limitation of presidential terms. This voluntary restraint became an unwritten rule for American presidents until Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four terms in the 20th century. Subsequently, the two-term limit was formally codified in the 22nd Amendment to the US Constitution, solidifying Washington’s initial choice as a fundamental aspect of American democracy. Therefore, to answer directly, George Washington served two terms as President of the United States, a decision that shaped the future of the American presidency.

References

[1] Jonathan Trumbull Jr. to George Washington, June 22, 1799, in The Papers of George Washington, W. W. Abbott, et al. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1987– ), Retirement Series, 4:144.